On the relevance of Marx in times of ‘Zombie Capitalism?’

Studying an author hermeneutically refers to understanding a writer by standing in their shoes and seeing the world from their perspective. Studying political writings in such a manner was advanced in the mid-20th century by scholars like those in the ‘Cambridge School’ of history of political thought.

When Karl Marx was writing Capital, in mid 19th century, the term ‘left’ (on the political spectrum) meant being ‘radical’ whilst ‘right’ referred to being ‘conservative’. The designations (literally positions or ’wings’) were taken from the post-revolutionary Constituent Assembly of France, with the colours derived from the Republican tricolour flag.

However, by the mid 20th century, during the post-war consensus, ‘the left’ was associated with support for state control of the economy and government social intervention whilst ‘the right’ had come to be associated with anti-state individualism and ‘liberalism’ (or Hayekian ‘market non-interventionism’). By the 1970s and ‘80s a new breed of ‘post-consensus’ right-wing politicians emerged who were deemed (in many respects correctly) ‘radical’.

Reagan and Thatcher were the most prominent ’radicals’ to have ideologies named after them (Reaganism and Thatcherism). Such radical right-wingers wanted to tear down what they saw as a ’statist’ establishment which, of course, many left-wingers wanted to ‘conserve’. The switch in meanings of left and right was completed in the form of conservative left-wingers (whether Bolsheviks, Maoists, Post-colonialists, Keynesians, Swedish Social Democrats, British reformers, or any other version of left ’state power’ grabbers who felt they had something to preserve, a status quo).

This kind of ‘conservative’ left statism was not unknown to Marx. Marx’s awareness can be detected in his many critiques of ‘utopian’ socialists during his lifetime, from Robert Owen to his Critique of the Gotha Programme (of the German Social Democratic Party, SPD). But Marx describes workers taking control of (rather than power over) society on very few occasions, with his most prominent account featured in news articles published (later) by Engels as The Civil Wars in France (1871).

This was Marx’s account of the rise and fall of the Paris Commune (1870). Importantly, what he describes in these articles is a delegate-based anti-statist workers’ council or commune system (the word ‘commune’ meaning grassroots council). ’Councils’ were both local (geographically-centred – the rural village) and vocational (workplace or activity centred – e.g., a weavers’ collective) to ensure different elements of society were heard, but significantly that no-one living off the private expropriation of production (performed by others) would be (easily) heard. This was a reversal of the prior situation where a separate class of politicians (who expropriated or represented expropriators, and even proprietors of private ‘labour power’) formed the state and government.

Furthermore, when Marx was asked if the ‘stage’ between pre-capitalist and communist societies could be by-passed or skipped, he eventually nodded to a positive answer regarding the development of existing Russian ‘communes’ (in a letter to a Narodniki). To be clear, I consider him hinting that ‘industrialisation’ and ‘urbanisation’ were not prerequisites to the fulfilment of some objectified ’inevitable’ historical progression working ‘at the backs of people’ towards ‘socialism’ and then ‘communism’ in a compulsory stadial trajectory.

As ‘communes’ already existed in Russia they could form the basis of an emancipated society, without a deranged detour through ‘capitalism’! However, Marx still thought that the experience of capitalism would be more likely to produce a social revolution, given the nascent conservatism of the rural commune – put another way, more advanced industrial countries should see a revolution first given the (contradictory) life conditions they generate. Also, given capitalism’s existence (historical arrival, even by accident) hopes of a direct transition from peasant communes were, simply, after the fact even in the mid-Victorian era. The social form that gave rise to such hopes (the peasant village eulogised by the Narodniki) was already disappearing, specifically in the advanced and developing industrial nations who had the power to colonise and suppress every other type of social form or mode of production.

Nevertheless, and this is a salient point, I would argue that for most (if not all) of his political life Marx was what would be known, in both 19th and 20th centuries, as an ‘anarchist’! The point of the Paris Commune’s mandatory delegation system was to ensure there would be no separation between a (professional) political class and the rest of the population. Thus, parliamentary ‘representation’ with its political leadership (elites or vanguards) was simply not good enough since it would reproduce one of the fundamental social / political divisions which Marx wished to see the back of.

Indeed, one way of outlining how Marx understood the ‘politics’ of capitalism, compared to feudalist and ancient slave modes of production, was that capitalism makes what was obvious in the others (direct political domination) an inconspicuous, or ‘hidden’, process (via indirect economic domination under the ‘guise’ of ‘fair’ trade – see Ellen Meiskins Wood, 2002).

But how did the previously noted transition in meaning, from the 19th century radical left / conservative right to the 20th century conservative left / radical right, take place? The answer, not surprisingly, was via successful social revolution in the early 20th century! The conceptual and analytical problem here is that all too often activists (those present at the time) and commentators (contemporary or later) have focused attention on the ‘trees’ whilst failing to see the ’wood’! Hence, we end up with histories and analyses of ‘The Russian Revolution’ (1917), ‘The German Revolution’ (1918-19), ‘The Hungarian Revolution’ (1919-20), but don’t hear much about ‘The Irish Revolution’ (1916), the Syrian democratic constitution (1919-20), ‘The Finnish Revolution’ (1917-22) nor ‘The British Revolution’ (1918-22). Generally, a global move towards universal suffrage, imposed from below as part of a working class revolution in political practice (namely, direct democracy), gets overlooked.

The dominant analytical time frames and intellectual interests tend to be centred on what can be described as moments of coup d’etat (significant but fleeting changes within forms of political ‘representation’) which merely punctuated much broader social changes. With the latter including changes in working practices, shifts in artistic practices and possibilities in communication, but also developments in social roles and recognition – the rise of married women in the workplace, the emergence of state welfare recipients (like working-class ‘pensioners’ in Britain), the emergence of ‘childhood’, and the extended legal reach of the state (such as compulsory purchase of land, military conscription, and nationalisation of banking).

One way of taking a wider survey of the workers’ revolution is to frame it in terms of all those socio-politico-economic changes taking place between the start of the Great War (1914) and a final capitulation of ‘traditional’ (pre-fiat money) capitalism in the Wall Street Crash (1929); a fifteen year period after which things can never go back to the way they were before though the desire to do so (right-wing radicalism) continues to be felt as an echo – the march of the Zombies.

Whether we understand ‘the revolution’ as having succeeded (the eventual emergence of the Soviet Union as a ‘workers’ state’) or failed (the crushing of the German Revolution by the freikorp in 1919), by the early 1930s states (and/or public, centralised institutions associated with them, such as central banks) are everywhere taking the lead role in forming (and/or reforming) the most advanced ’capitalist?’ economies. From here on, I place a question mark on ‘capitalism?’ to indicate the far-away hills distance of the classic liberal model or mode. Both the ideology and practice of classical ‘liberal’ political-economy was ’dead’ but also ‘alive’ as a zombie.

Whereas before 1914 capitalist enterprises mostly got on with the job of reproducing, disciplining, exploiting workers in an autonomous manner (with little to no state intervention), by the early 1930s the state becomes, increasingly, an integral part of the social process, including the production of surplus value (profit) via a national organisation of surplus labour time (e.g. how to manage unemployment). States did take different forms, such as ’total‘ states (a singularity, as in the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany) compared to ‘hegemonic’ ones (pluralities dominated by mass cultures and technocratic control), but the main task of all states / governments was to reproduce (provide subsistence to), discipline, and (successfully) exploit workers directly as the key means of sustaining the wage-labour mode of production. The purpose of the modern nation-state, after all, is to ensure the compliance of the population (whether worker, manager, capitalist, or politburo member) under its territorial control with the accumulation of capital.

By exploitation, of course, I include the ideological elements of emotional exploitation (something Gramsci picked up on as hegemonic cultural domination): “Heave away lads, put your backs into it, for the benefit and sake of the nation!” A new ‘social contract’ between political elite (the state) and the people (workers) was being founded, and in many experimental forms – Soviet Communism, Italian Fascism, Japanese Imperialism, Irish and Finnish nationalism, German Nazism, the American New Deal, Jewish Zionism, and ‘Greater’ Britishness (re-modelling the Empire as ‘Commonwealth’). The last of these was even mooted, at one point, as a new country, called Greater Britain.

Some of these were ethno-nationalist (Nazism / Zionism) whilst others were pan- or trans-nationalist (the Soviet federation and British unionism), but almost all (excepting the smaller nations) led to expansionism (ultimately, war). In contrast with the era of joint-stock ‘liberalism’, state-control of economic and social life was now in the driving seat. Many of these subsequently failed (losers to others in war) and the leading ideologies emerged as those of (Western) ‘Keynesianism’ and (Eastern) ‘Communism’, with a common connection in ‘state-led’ social formation. It is not inaccurate to describe the outcome as socialism, with socialism as the natural religion (‘binding’) of capitalist alienation.

In this sense, ‘a’ social revolution did take place in the early 20th century, but one with a compromised, synthetic outcome. In Gunn and Wilding’s (2022) Hegelian terms: mis-recognition pertained. Workers gaining universal suffrage in Britain was ‘a revolution’, but one that is almost always overlooked! Sometimes the achievement of suffrage is deemed a mere ‘concession’ by a ruling class determined to retain their power through more subtle methods (the hegemonic control of education and broadcast media, as pinpointed by Gramsci’s early analysis of Italian Fascism). But to rob the period and Gramsci of their ‘openness’ produces an historiography which makes the ruling class ‘oh-so clever’, as if it was their ‘Revolution’.

More tellingly, the same social revolution produced a crisis in surplus value production (and the rate at which accumulation could proceed) – the Wall Street Crash both questioned the emerging fascist conceptions of a ‘New Man’ (much admired by elite figures such as the British Royals: Edward Prince of Wales and Albert Duke of York) whilst also hastening change. As Thomas Piketty’s (2018) empirical data has demonstrated, before 1914 capital accumulation grew at a rate faster than wage growth, but throughout the mid-20th century the reverse was true (wages grew faster than profits). ‘Capitalism?’ had been saved by socialist collectivism (the amalgamation of multiple capitals into a singularity), but at massive economic and social (status) cost to the conventional ruling class and its practices. Workers, in their role as waged workers (subjects central to the accumulation system), had imposed their interests and gained decision-making power within the capitalist state mechanism, even if their so-called ‘class consciousness’ remained ‘corrupted’.

In his overview of Keynes’ theoretical work, and reformation of capitalist strategy, Negri, in Revolution Retrieved (1988), coins the term positive Keynesianism to refer to the immediate post-war period (1945-1973) when state welfare benefits and full employment policies were used to encourage and entice employees to work hard and raise their productivity. This ever-rising productivity was central to the strategy and was baked-in to a social necessity for endless economic growth and, so long as the economy could be grown at a sufficient rate, the fact wage earners (as property owners) were making distributional ground on recipients of profits, rents and taxes was an acceptable trade-off, especially as any class relying on unearned income was on the back foot. But with ‘stagnation’ in the 1970s the situation grew desperate for profiteers, rentiers and public servants (tax-takers) meaning something needed to be done – the rise of the right-wing radical was witnessed just as open ‘class conflict’ surfaced or re-emerged.

This conflict produced a shift in the social contract, but not one from Keynesianism back to Liberalism, despite the hopes of the radical right-wing ideology known as ‘Neoliberalism’. Rather, Negri describes the shift as one towards negative Keynesianism. That is, rather than the state taking a reduced and fading (or to use Marx’s phrase, vanishing) role in ‘the economy’, which is what Neoliberals like Thatcher may have ‘thought’ was going to happen (or wished would happen in a return to the ‘classic’ era), negative Keynesianism maintained levels of state intervention in social life (and its prominence in guaranteeing the reproduction, discipline, and exploitation of the working class).

Instead of positive encouragements (material benefits; socialised myths of ‘we are all in it together’), negative Keynesianism ‘liberated’ the representatives of monied-capital only by ‘oppressing’ worker dissent to capital’s imposition that people remain ’waged labour’. Militarisation of society (higher prison populations; investment in security, securitisation, and surveillance), the piling on of indebtedness (for housing, education, and health), and creeping isolation (social individualisation and insulation: gated communities; financial ‘independence’) were the negative Keynesian modes of operation.

So, what is the importance of the above analysis of social change over the last 100 years with regards to studying Marx’s Capital? On the one hand, when we read Marx via his original writings his anti-statist (radical) position must be kept in mind – his anarchism means he was against political systems containing social divisions between rulers and ruled. He would have been appalled by the ‘Soviet’ regime produced not just by ‘Stalin’ (that is too easy a cop-out) but Bolshevism from its inception (in 1892). Marx would have recognised the ‘council communist’ and even ’liberal democratic’ revolution that occurred in Russia in Feb (or March) 1917 as progressive whilst reserving criticism for remnants of expropriator influence and power.

Whilst Bolshevism did get a ‘populist’ upper-hand on (the more ‘reformist’) Menshivist movement (largely related to ending the war immediately), leading to the ‘October Revolution’ (a coup d’etat), the dismantling of the Soviet (‘council’) system and democratic ‘reforms’ happened very quickly under Lenin’s centralisation of political institutions. The democratic arrangements of Feb-Oct 1917 may not have led to a ‘non-statist’ system, as Marx would have desired, but they could have produced a different outcome for both Russia and Germany in the 1920s (Luxembourg did not feel the time was right for the kind of ‘coup’ attempted by workers in Germany). Probably the ‘revolution’ would have developed more along lines of what happened in the Western world. Marx reserves his ‘ire’ for statist politicians of all shades in his political writings, as well as those who try to ‘force’ history and recognition forward (e.g., the professional ‘revolutionary’)!

On the other hand, a standard objection to taking Marx seriously is that, given all the social and technical ‘change’ that took place during the 20th century, surely Marx’s writings are limited to the kind of 19th century capitalism he witnessed (of the classic liberal type)? Namely, he is good at excoriating Mr MoneyBags, the woefully selfish carpetbagger and child-exploitative industrialist of Victorian slum cities, but modern capitalist corporations are operated by equality, diversity and inclusion-qualified executives who are socially aware and just don’t operate in the same way as the Victorian businessman! I would point out that whilst Marx is often associated with writing a ‘grand narrative’ (an overarching account of the large sweep of history, a la The Communist Manifesto) his study in Capital is highly specific.

Capital is an examination of just one type of social relation (or mode of production) – the wage labour / capital relationship. Marx’s work analyses (breaks down) this relationship and identifies its complex and multifarious derivative forms – that is, if we find ‘the commodity’ (which is produced and appears everywhere in daily life – part of our immediate experience) then we will also find both mutual recognition and value (defined as socially necessary labour) – anyone producing ‘commodities’ must recognise others as equivalents (owners) and produce at a socially-recognised rate (e.g., items per hour).

If we then find that human ‘labour power’ is one of the commodities available for purchase, then we will find ‘surplus value’, which is produced via ‘absolute’ and ’relative’ processes, and so on. The argument in Capital Is not an ‘historical’ story but Marx’s way of laying out a conceptual ‘unfolding’. One difficulty, compared to earlier classical political economists, is in getting the order of conceptual presentation correct, so that the reader does not go off on the wrong foot by starting with something which is ‘derivative’ (e.g., ‘profit’).

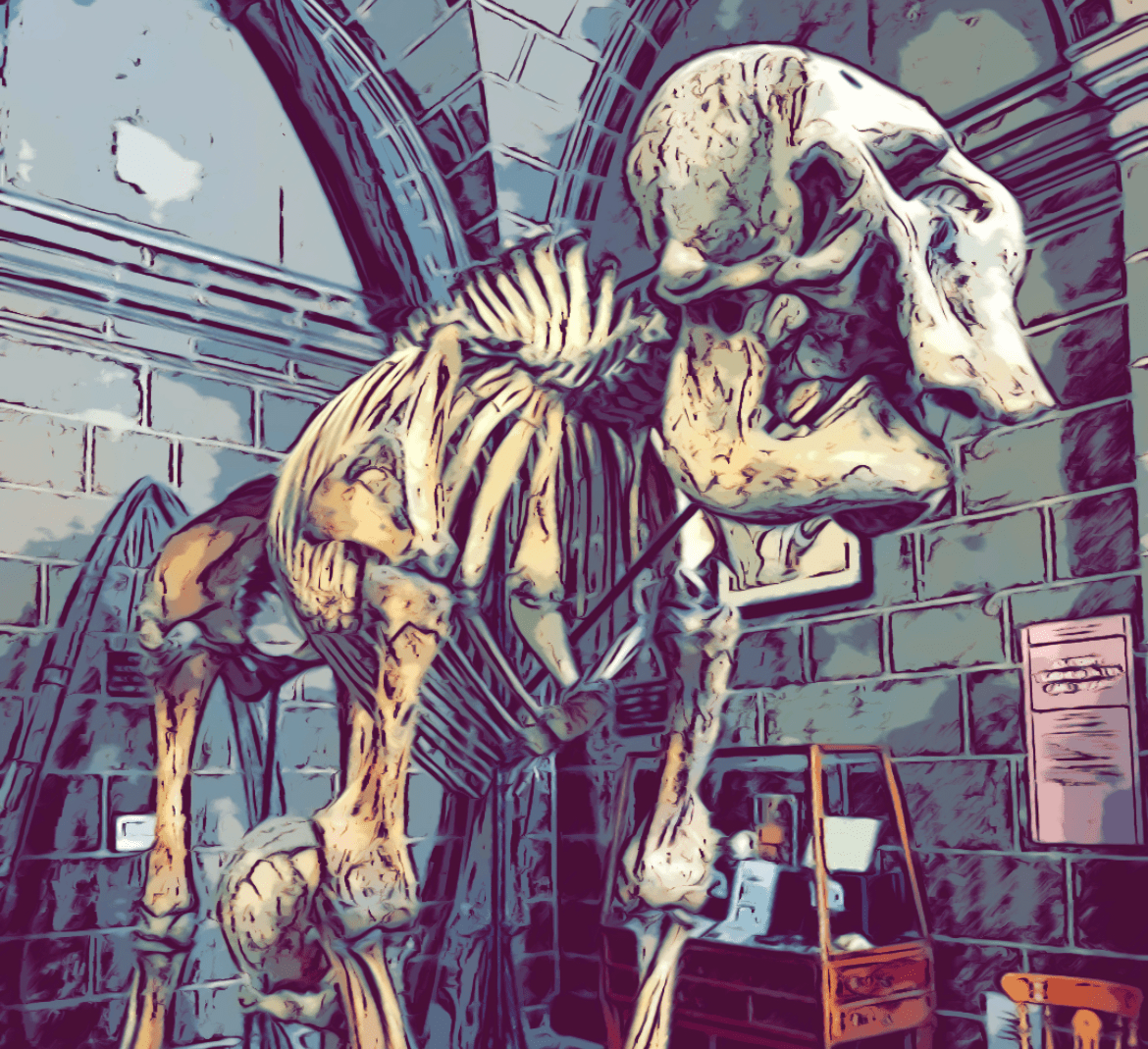

In summary, Capital is a study of one kind of social relation, and wherever that social relation (waged labour) is found then Marx’s analysis remains applicable, no matter how technologically-advanced or different a ‘society’ might happen to appear. The main question, therefore: is ‘our society’ still based on waged labour (capital)? If so, then Marx’s Capital is [remains] relevant. The flesh of the elephant may have fallen away, but to the trained anatomist what stands before them is still an elephant.

Publication Note:

I wrote (started) this article in February 2024, but it then lay dormant and unfinished (on my cloud drive) until September 2025. Reading my friend Werner Bonefeld’s (2023) book (A Critical Theory of Economic Compulsion Routledge) inspired me to return to it and at least publish, in a still unfinished form (the referencing is incomplete; if / when I get the time I will return to this element).

References:

Bonefeld, W. (2023) A Critical Theory of Economic Compulsion: Wealth, Suffering, Negation London: Rutledge.

Gunn, R. & Wilding, A. (2022) Revolutionary Recognition

Negri, T. (1988) Revolution Retrieved

Piketty, T. (2018) Capital in the 21st Century

Wood, E. M. (2002) The Origins of Capitalism: A Longer View